Meet the mountain

One of the many reasons I want to meet Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania in just over a year's time is her sheer variety.....geology, geography, climate, flora and fauna, she's got them in spades. I think it could be a pretty painful date but it almost certainly won't be boring finally meeting her

I wrote about Henry Stedman's excellent Trailblazer guide in an earlier article (Yes, but which way up?). Henry has been enthralled by Kili and claims to know her better than anyone else. His book is full of wonderfully alluring detail that I'd recommend reading, whether you ever have any intention of going to Tanzania or not

There is also a very good briefer book on Kili written by Jacquetta Megarry and published by Rucksack Readers. I'm going to quote shamelessly from this book (in italics) with my own annoying thoughts noted alongside (not italicized) to try and give you an idea of how we'll experience the world's extremes in 7 days on Kili next February. I guess this is a copyright infringement but I'll get in touch with Rucksack after publishing this article and hope that they'll be happy with the free plug in the meantime

5 zones encircle the mountain for about 1,000 metres of altitude, each with its own climate, plant life and animals. The higher you go, the colder it gets and the lower the rainfall, limiting the number of species. These conditions demand remarkable adaptations for survival

1. The lower slopes

(Our Machame route starts at Machame Gate at 1,800m altitude but we'll experience the lower slopes during the drive from the town of Moshi to the start of our trek. More on the detail of our scary itinerary in a later article)

(Our Machame route starts at Machame Gate at 1,800m altitude but we'll experience the lower slopes during the drive from the town of Moshi to the start of our trek. More on the detail of our scary itinerary in a later article)Between about 800-1,800m the Chagga people cultivate the rich volcanic soil for crops such as maize, coffee and bananas. The south and west sides of the mountain are wetter and more fertile, with rainfall varying from 500-1,800mm (20-70 inches) each year. (The Machame route is on the south side of Kili)

There are brilliant wild flowers and interesting vegetation supporting a wide range of bird life, including the common bulbul (brown with a black crest), the tropical boubou (didn't he used to be a mate of Yogi Bear's?), lots of brown speckled mousebirds and nectar feeding sunbirds (long curved bills and iridescent feathers)

2. Rain forest

The rain forest occurs between about 1,800-2,000m, with rainfall of about 2,000mm (80 inches) per year on the southern slopes. The west and north are much drier, and on the Rongai route the rain forest is sparser and less luxuriant (see the earlier article "Yes, but which way up" for a summary of each route). The forest often has a band of clouds, with mist and high humidity. Fine tall trees are decked with streamers of bearded lichen. Mosses and giant ferns flourish in these conditions, and wild flowers include violets, the occasional orchid and the unique red-and-yellow Impatiens kilimanjari, found nowhere else in the world

Common huge trees include Podocarpus milanjianus and camphorwoods. In the upper forest you start to see giant heather trees with yellow-flowered hypericum (St John's Wort) growing among them. Protea kilimandscharica is common around Maundi Crater and above Mandara

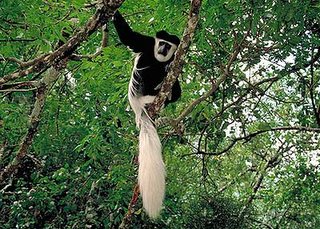

Fruit trees attract many birds: if you hear a bird braying like a donkey, it's probably a silver-cheeked hornbill. If you're lucky enough to see a large bird flashing crimson at its wings, it could be a turaco. Most animals are shy and easily hidden in the thick vegetation. You will probably see monkeys in the forest: blue monkeys and colobus (black with a flowing white mane of hair and thick white tail)

3. Heath and moorland

Between 2,800-4,000m are overlapping zones of heath and moorland, with rainfall ranging from 1,300mm (50 inches) a year on the lower slopes to 500mm (20 inches) higher up. Frost forms at night, and intense sunshine makes for high daytime temperatures

Heather and allied shrubs are well adapted to these conditions, the giant heathers (Erica arborea) having tiny leaves and thick trunks and growing to 3 metres high. You'll also see red hot pokers (Kniphofia thomsonii) standing to attention, and colourful Helichrysums

The moorland is dominated by giant groundsels (senecios and lobelias), especially near water courses. The most striking is Senecio kilimanjari, which grows up to 6 metres tall

The animal you are most likely to see is the tiny, semi-tame four-striped grass mouse (Rhabdomys pumilio), which has found its niche around the Horombo huts. From just above the forest upward, you will often see and hear the harsh croak of the white-necked raven, which scavenges successfully from the huts

4. High desert

The montane (high or alpine) desert zone stretches from 4,000m-5,000m and has low precipitation, less than 250mm (10 inches) a year. Here summer burns every day with mid-day temperatures of 35-40C (throw another shrimp on the barbie, Steve), whilst at night the winter chill bites deeply (unpack the long johns, Mrs M). Soil is scanty, and what little there is can be affected by solifluction; when the ground freezes, it expands and flows, disturbing plant roots. Only the hardiest can survive, such as the long-lived lichens (and hopefully The Kili 5)

The few plants that survive are slow-growing so care should be taken not to damage them

5. The summit zone

Higher up it is colder and drier still, and the slight precipitation (under 100mm or 4 inches a year) falls mainly as snow. This often condenses from clouds sucked up from below when air pressure drops because of the warming effect of the sun. There is no liquid water on the surface: it disappears into porous rock or is locked in as ice and snow

Living things must not only endure the blazing equatorial sun by day, but also arctic conditions by night. Here altitude defies latitude. With deep frosts, fierce winds, scarce moisture and less than 50% of the oxygen available at sea level, the environment is deeply hostile to any kind of life. Remind me why we're attempting this again.....

The highest flowering plant ever recorded was a small helichrysum in the crater at 5,670m. Animals are very rare, although in 1926 Richard Reusch found and photographed a snow leopard frozen in the snow. Hemingway immortalised it in his 1938 short story The Snows of Kilimanjaro, remarking that "no one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude"

So there you have it. 1 mountain. 5 zones. A world of extremes. All in a week. Sounds amazing and scary in equal measure, eh? Stay tuned to this blog to see how we progress over the next 13 months until next February and the most interesting date any of us have probably ever been on (apart from when we met in The Old Emporium in Fleet obviously, Gill)

1 Comments:

Bonjour Mr Morris and the Kili 5. No idea what this blogging malarkey is all about, but keep reading about them in the papers.

Keep up the training, (and will you ever do any work at all in between all your very informed and interesting blog entries???)

Do tell what these HMTL tags are all about too....

Blog Virgin Watty xx

Post a Comment

<< Home